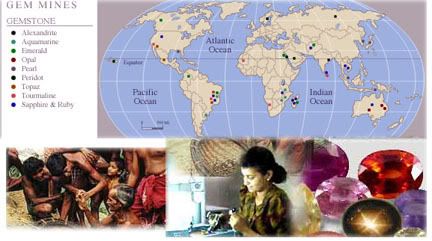

Transparency In The Colored Gemstone Trade?

Introduction:

Laurent Cartier asked me in the previous post how complete transparency is possible in your supply chain, apart from saying that somebody brought you a stone and you paid him a fair price.

Three models currently exist where we can have trusted transparency from the artisanal miner to the marketplace. Each of these scenarios involves a great deal of trust. The dealers have to assure that they represent their standards and procedures accurately.

In some of these scenarios, what we have is second party verification, rather than third party certification of procedures. The person who is selling the gemstones assures that standards are being upheld. At this point, I believe that those involved in these early efforts, these change agents, act on behalf of their own personal values because the market has not valued higher ethical standards.

The first scenario involves developing cooperatives and third party organizations that work with the artisanal miners to develop standards. The Association of Responsible Mining (ARM) for example, provides transparency in the supply chain by supporting the efforts of miners.

TransfairUSA’s study of diamonds, if it amounts to certification, might also be considered as part of this category. But if their efforts are directed toward large scale diamond mining then they will end up, in effect, blessing the ‘fair wash’ companies which have an onerous history.

(Transfair is not working with ARM, which seems counter intuitive, except when you consider how difficult it is to work with small scale miners and how easy it would be to just put a fair trade tax on diamonds and fair way one of DeBeer’s well run mines.)

A second example involves pioneers such as Eric Braunwart of Columbia Gems who has developed the resources to contract with governments and mines to create a fair trade based system with a select group of stones. He does his cutting in China. Many suppliers and retailers heavily depend upon Eric’s company.

There are huge opportunities right now for someone to do what Eric has done in the lower end scale. If I had the resources and time, I would consider doing something in India with garnets, amethyst, peridot, etc… all the basic “semi-precious” around transparency in sourcing and cutting.

I use these gemstones and I’m disturbed to hear accounts of some of the cutting factories around Jaipur. At this point, I cannot do much since these are core elements of the production line in my company. If someone could develop some higher standards, it would fill a huge gap in the supply chain because right now this movement is geared toward the luxury market.

A third example includes working with individuals who contact the miners and develop relationships based upon a fair trade ethos. I work with one individual who has painstakingly developed a direct relationship with miners in Zambia.

One particular village where my contact now sources excellent emeralds had actually closed their emerald mine for years because they were no longer willing to deal with unscrupulous dealers. His commerce now supports schools and AIDS drugs for the village as a whole. This person takes his stones to a particular cutting factory in Thailand that is spot on.

One could argue that third party assurance is necessary in order for these efforts to be credible, but I am no longer sure of this.

At some point, radical transparency and the blogosphere may ultimately trump third party transparency. Quoting from an article written by Clive Thompson and published in Wired Magazine in April, 2007:

“Secrecy is dying. It’s probably already dead. In a world where Eli Lilly’s internal drug-development memos, Paris Hilton’s phone-cam images, Enron’s emails, and even the governor of California’s private conversations can be instantly forwarded across the planet, trying to hide something illicit—trying to hide anything, really—is a gamble. So many blog rely on scoops to drive their traffic that muckraking has become a sort of mass global hobby.”

Radical transparency allows the customer to determine whether the standards are true.

Fair Labeling Organizations (FLO) have their bias. Not all the organizations under FLO agree about their approaches. Who is to say that they cannot be co-opted from their original mission of helping disenfranchised artisanal miners by the huge amount of money available by putting a fair trade tax on diamonds in a Rio Tinto mine, for example?

The issues are complex and the conversations in which policies are being worked out are private. When the final standards are worked out, it will be presented as an authoritative model.

The people who are in my supply network feel as strongly about ethical sourcing as I do. This circle is so small at this time that most of us are well known to each other. I am not concerned about third party assurances. Developing these contacts is the work I have to do for my customers in order to connect their money to an economic set of relationships that is fair right down to its source.

We need to consider how we can bring in as many different types of scenarios that have the highest ethical standards possible. Just focusing on a few with “fair trade” third party certification will never be enough.

With our spotty supply chain and so few people doing this type of pioneering work, it is like trying to build circles out of triangles.