Human Rights Watch está detrás del Bling: Un análisis estratégico

“Conoce al enemigo y conócete a ti mismo; in a hundred battles you will never be in peril” —Sun Tzu

(This excerpt from Marc Choyt’s Ethical Jewelry Exposé: Mentiras, Damn Lies, y diamantes libres de conflicto; was originally published aquí.)

En febrero de 2018, Human Rights Watch publishedThe Hidden Cost of Jewelry, y puso en marcha su campaña #BehindTheBling. Theircall to action was signed by 29 non-governmental organizations (ONG), incluyendoAmnesty International, Global Witness, yIMPACT (formerly Partnership Africa Canada.)

The report documents human rights, trabajo infantil, and environmental atrocities associated with large players in the gold and diamond industry, and offers a rating system: excellent, strong, moderate, weak, very weak, and no rating.

Noting that several of the large companies are members of theResponsible Jewellery Council, the report states, “Many companies are over-reliant on the Responsible Jewellery Council for their human rights due diligence. The RJC has positioned itself as a leader for responsible business in the jewelry industry, but has flawed governance, standards, and certification systems.”

As mentioned, there is a consumer-facing campaign attached to this study—and the study itself is addressed to the broader jewelry sector. But the Responsible Jewellery Council—an organization with over 1,100 members—is a central focus of the report.

This case study will explore how the Human Rights Watch critique of the Responsible Jewellery Council actually empowers the Council; and why #BehindTheBling not only fails to activate thereal energy for change, it undermines it.

I’ll conclude with a call to action that I believe would, with NGO support, seed real change in the marketplace.

The Responsible Jewellery Council/NGO Dance

For many years, the Responsible Jewellery Council has needed the support of NGOs to legitimize its efforts and to address reputational risks.

Some of the NGOs that work with the Responsible Jewellery Council arecompletely collaborative. Others, tales como la 29 signees to the HRW’s call to action, engage with the Responsible Jewellery Council as a focal point in an attempt to change the world, part of their raison d’être.

Within this context of Responsible Jewellery Council/NGO interaction are variations ofradical centrism. But to move issues of common concern forward requires that both parties have an equal footing. A power dynamic that engenders positive change also depends upon a deep level of honesty, respect, and willingness to compromise.

What’s particularly tricky isthe present moment. In personal relationships and negotiations, small signs of bad faith can be easily bypassed by the optimism of the possible. It’s hard to see the shadowy movement on the peripheral of your vision just as daylight is swallowed by the night, especially over a glass of fine wine.

Además, actions themselves can often only be understood in context over a period of time. Without an ongoing assessment of the power shifts, interdependence can become codependence. Critiques, even valid critiques, then have diminishing returns. Worse, they can actually be enabling. If a lasting solution is to be achieved, theremust be transparency and respect.

Ahora, once an agreement is reached, whether it results in the desired outcome can only be determined over time. A radical center compromise without fully “knowing the enemy and knowing yourself” can become a slippery slope.

Let me give you an example of what I mean:

NGO Responsible Jewelry Faustian Bargain

As mentioned, Global Witness and IMPACT are both signees on the Human Rights Watch report. These two organizations have a long track record of interacting with the jewelry sector, particularly in context to diamonds.

De hecho, they were both engaged in the formation of the Kimberley Process, which, asI’ve pointed out, has two main components: the scheme itself and the powerful “conflict free diamond” consumer-facing narrative.

Ahora, here’s what is key in understanding our present moment:

When they sat across from major players in the diamond sector to create the Kimberley Process, these NGOs represented core human values. They were facing an industry that was complicit in funding wars that resulted in the deaths of 3.7 million people.

I remember attending the industry-leading JCK trade show in 2006 when the Blood Diamond film was coming out. I was thinking, “who among those walking about in their fine suits was responsible for these actions?"

I still have that question today.

ONG, parece, did not insist upon truth, reconciliación, and restitution. (As I’ve previous argued, what we need to see is support for economic development in terms of emphasis of best practices and increased access to international markets.) A consecuencia, NGOs have enabled the Responsible Jewellery Council in a pattern of denial.

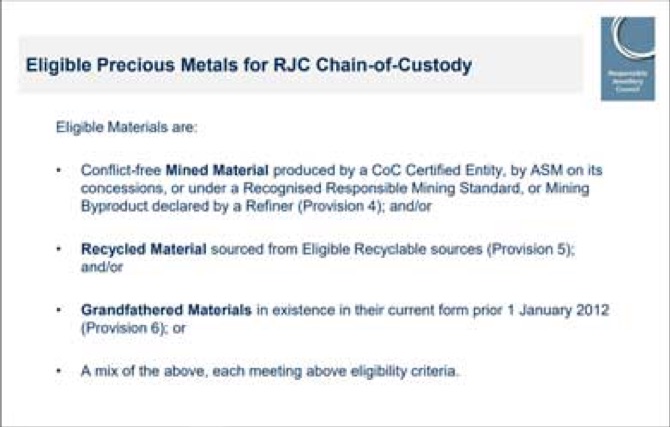

Any new protocol for “responsible jewelry” must be flawed because of thisGrandfather clause, because, past is prologue.

As Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar; it comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.”

Así, nothing was gained by that concession in context to an improvement in the lives of small-scale miners.

Martin Rapaport calls the Kimberley Process “bullshit.” The term “Conflict Free Diamonds,” which is based upon the Kimberley Process, remains the keystone of the forward-facing consumer narrative used to sell diamonds, despite the repugnant morality that you can create a “conflict free diamond” narrative without truth, reconciliación, and restitution for impacted communities.

Además, as documented in my exposé, the Responsible Jewellery Council is nowturning gold from companies with documented alleged atrocities into ethical gold.

The radical center approach, the notion that there can be real change in the mainstream jewelry trade’s focus through negotiation, is no longer convincing—simply based upon the evidence of the last fifteen years.

De hecho, the negotiations, the engagement, becomes a kind of strategy for the sector to actually deflect NGO critiques.

Human Rights Watch suggests this same conclusionaquí, stating that industry’s “lack [de] serious engagement with the true task at hand” fails to tackle human rights abuses or develop scalable solutions for artisanal mining communities. Quoting further: “Given recent and past experience of industry engagement, we are concerned that such efforts are being used to distract from the need for meaningful industry-wide progress.”

De hecho, because truth, reconciliación, and restitution have not been in the center of non-governmental organizations’ strategy, they are now enabling the Responsible Jewellery Council’s consolidation of power by engaging with them.

In the new ethics, even the methods of critique offered by industry watchdogs are a continuity incorporated into a rebranded narrative which is merely a cover up for a greater lie: the perpetration of neocolonial practices which too often treat people and place in “shithole countries” as commodities in a resource to cash to trash economic model.

Let’s see how this plays out in practice:

The Witch’s House

In the past, broad attacks against the jewelry sector, as represented by the Responsible Jewellery Council, drew respectful rebuttals and engagement.

For example—in May, 2013, More Shine Than Substance was published byMovimiento de tierras, in conjunction withMining Watch Canada, Construction Forestry Maritime Mining and Energy Union, yUnited Steelworkers. The study’s main focus was a critique of the Responsible Jewellery Council. The Responsible Jewellery Council very quickly issued athorough response. En aquel entonces, they had about four hundred members.

Ahora, five years later, they have over 1,100 miembros. We can only conclude thatMore Shine Than Substance had no impact on the Responsible Jewellery Council’s momentum and strategy to maximize profits for its members.

Hoy, the Responsible Jewellery Council has consolidated their power to such a degree that NGO critics seem to have even less influence—or at least, their criticisms worry the Responsible Jewellery Council less.

La 2018 Human Rights Watch reportThe Hidden Cost of Jewelry drew a very minimal response, which was issued mainly thoughthe trade press.

De hecho, the Responsible Jewellery Council didn’t even respond to the Human Rights Watch directly. En lugar, we have this:

The CEO of Signet, a Responsible Jewellery Council member with3,356 stores, Virginia C. Drosos, escribió, “In the spirit of transparency and cooperation, Signet and other members of the jewelry industry engaged openly and extensively with Human Rights Watch. Desafortunadamente, the report contains language chosen more to criticize our industry rather than provide constructive recommendations.”

She uses Human Rights Watch’s past engagement against them.

Here’s my takeaway:

This is the fruit from the harvest that comes from Human Rights Watch’s not understanding their enemy. For many publicly-traded companies, the only thing that matters is the bottom line. Human Rights Watch thought that they were exacting change—when in fact, they were merely being used.

In the Witch’s House

Let me use another metaphor to make my point:

Virginia is analogous to a wicked witch in a fairy tale. You may think she’s merely flying about on her broom, but actually she’s practicing marketingaikido.

Constructive criticism lifts her like an updraft as she circles about the Responsible Jewellery Council castle below.

In claiming to have an open consultancy process, she invites us into her Responsible Jewellery Council house of mirrors, where everything you say is merely reflected into incoherent fragments of labyrinth.

Behind the tree are the goblins—analogous to Gerhard Humphreys-de Meyer, the Responsible Jewellery Council Communications Coordinator.

“We have reviewed the Human Rights Watch report and reject the suggestion that Responsible Jewellery has got ‘flawed’ standards, governance and certification systems…HRW has itself acknowledged the Responsible Jewellery’s progress in making jewelers more aware of the importance of responsible sourcing and getting them to adopt more responsible practices,” he tellsRapaport News.

Goblin David Bouffard, Signet’s VP of Corporate affairs, calls for “HRW to engage more constructively with the Responsible Jewellery Council and other participants in the jewelry industry.”

(At its 2018 General Meeting, Bouffard was anointed the new Responsible Jewellery Council board chair.)

Engage constructively. Isn’t that what Human Rights Watch and others have been attempting to do for the pat decade or more?

Human Rights Watchknows that the Responsible Jewellery is not a straight player. Within the HRW report is this statement: “The RJC consults civil society and other actors and includes civil society representatives on its standard-setting committee, but is essentially an industry body.”

This is not a new revelation. It has been the case for almost ten years!

Even back in 2009, six months prior to the Responsible Jewellery introducing their standards, Responsible Jewellery Council CEO Michael Rae admitted in anexclusive interview I publishedthat the Council is a “a trade association with a product stewardship focus.”

Yet we have to ask, ahora, why would Human Rights Watch or any of their group want to sit across the table from someone who has not shown good faith to the NGO community for so many years?

The past decade demonstrates that the radical center methods of working with the jewelry trade for reforms have not yielded the desired results—with one exception, Earthworks’Initiative For Responsible Mining Assurance.

Effective Radical Centrism

The most effective example of radical centrism in the jewelry sector is Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA). I would argue that their ability (as an environmental activist group) to credibly create a standard for large-scale mining companies comes at least in part out of theirNo Dirty Gold Campaign—which was launched in 2004.

Con el tiempo, Earthworks fully engaged the ethical jewelry community—even giving ratings to small jewelers which they could post on their websites.

It also supported change agents within the industry. The simple, three-word phrase “No Dirty Gold” is catchy, consumer-facing, and a powerful call to action foractivist jewelers yprogressive suppliers to employ. Even today, when I reference “No Dirty Gold” to customers at my store, they get it.

The Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance is not solely involved in supporting responsible large-scale mining. Their work echoes out into the world in unexpected ways. In my home of Santa Fe, Nuevo Mexico, where Earthworks helped medefeat a proposed gold mine, our county is currently considering using some of Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance’s language in a revision of its hard rock mining ordinance.

Movimiento de tierras, as I mentioned above, also was one of the publishers ofMore Shine Than Substance, and that study had no impact on the Responsible Jewellery Council’s growth and momentum. Nor did the publication ofEdificante La Tierra en 2011, which I helped to sponsor and publish on my Fair Jewelry Action website. (Like Human Rights Watch’sThe Hidden Cost of Jewelry, Que eleva la Tierra critiqued ten major jewelry brands.)

There’s no denying thatThe Hidden Cost of Jewelry is a powerful and compelling publication. But it uses tactics that already were shown to have minimal impact on consumer behavior—or tactics which, more essentially, fail to change the narrative story around jewelry.

Más, it’s my opinion that the term #BehindTheBling itself is too vague, and fails to stand out in the sea of ethical activist hashtags. #NoDirtyGold conveys a clear message in three words. #BehindTheBling, in contrast, could easily be confused as a story about making jewelry in my studio, or any number of other things.

Another issue: Earthworks’ #NoDirtyGold engaged activist jewelers, the grassroots change agents, and used the jewelry sector to amplify their messaging to the broader consumer market.

Human Rights Watch missed this opportunity to reach out to allies and amplify their message. I found out about their report from group email, a kind of who’s who list of ethical jewelers globally, cuandoThe Hidden Cost of Jewelry came out.

The buzz lasted less than a week—some discussion and a few posts. What a wasted opportunity.

The Seduction of Ineffectiveness

Perhaps the most critical flaw in the Human Rights Watch’s report is that it fails to locatethe energy for change in the market.

Instead of giving a clear call to action, Human Rights Watch offers a broad unfocused list that only a policy wonk onGoxi would be interested in reading and digesting. Its lack of focus is part of the reason why you could find a related editorial inUSA Today intitulado, “Attention Valentine’s Day shoppers, that jewelry might have a bleak backstory.”

“Might” have a bleak backstory? Realmente? It’s this sort of positioning that undermines the value of the whole report.

Again: the report does not have a strong, inspiring, consumer-facing call to action. Readthis articlein UK’sJewellery Focus. Jo Becker, the advocacy director for Human Rights Watch’s children’s rights division, lists lack of stakeholders, lack of transparency, and weak standards as major issues. She then states:

“We are committed to continuing that mission to drive improvement in responsible behaviour across the jewellery industry. The standards themselves are internationally recognised as robust and are continually open to comprehensive and transparent review to ensure they continue to advance the cause of responsibility in the industry.”

How are we going to create that change?

On what basis does Human Rights Watch believe that sending thesesuggested tweets out to companies is going to make a difference? “Thanks @Cartier for sourcing directly from gold mines in Honduras with high standards. But please do more to ensure all your gold and diamonds are fully traceable, and publish the results of your audits. #BehindTheBling”

Gracias, Cartier. Yeah, that’s really going to fire up the Gen Z and Millennial activists…

Buried in theircall to action is this one critical point, that jewelers should: “Actively seek out opportunities to source gold and diamonds from artisanal and small-scale mines that are not associated with human rights violations and willing to engage in credible legalization and formalization processes.”

En este contexto, the most effective disrupter in the entire jewelry sector has been Fairtrade Gold. I’m not saying Fairtrade/Fairmined Gold for a reason. Fairtrade is simply a stronger consumer-facing brand and has been proven to be the market choice in the UK. I’m saying it has to be Fairtrade Gold because the Fairtrade label is a powerful global brand that changed the consumer perception of chocolate, coffee, bananas, and other products.

Fairtrade Gold also has essentially changed the jewelry narrative in the UK. Ethical jewelry = Fairtrade. In the US, sin embargo, ethical jewelry among the mainstream =recycled product.

We need to create a broad Fairtrade Gold movement in North America to create a new narrative that accelerates regenerative economic models in the global south.

Yet the report endorses jewelers’ use of recycled metals as a viable “ethical” alternative. Really?

I’ve made this argumentelsewhere in the Exposé, but it’s worth repeating here:

The recycled gold story is one of the foundations of the ethical jewelry story in North America, and I was an early advocate for it back in 2007. At that point, it was the best a jeweler could do.

Sin embargo, recycled gold isno longerthe best we can do. Recycled gold was useful in raising awareness of sourcing issues—but ultimately, itbenefits neither the environment nor small-scale miners. Desafortunadamente, it is still being used as the ethical solution by the major supply houses in North America, including Stuller and Rio Grande.

That Human Rights Watch would call recycled gold a solution illustrates that they do not understand the ethical jewelry market. That’s an unfortunate oversight.

Here’s the problem:

Analysis of the jewelry sector in context to human rights and environmental improvement involves grasping not only human rights and environmental issues, but a complex system involving the broader market, market niches, supply chain issues, small-scale and large-scale mining, consumer-facing narratives, bloggers and journalists in the trade and consumer press, and the ethical jewelry market in context to precious metal, diamantes, and colored stones.

It is complicated. You have to be on the inside to understand this gestalt.

NGOs and activist jewelers—and here I’m excluding those who are aligned with the Responsible Jewellery Council or Fairmined, which endorses Responsible Jewellery practices—need to work together.

We need to create a strategy that impacts the bottom line of Responsible Jewellery retailers. Attacking profit margins is the only thing that will create the possibility of change which I detail in my call to action, El Manifiesto de la joyería ética.

Here’s The Way Forward:

Primero, NGOs have lost an opportunity by not focusing on their core strength. Their attempt to work with the Responsible Jewellery Council must be based upon a moral high ground that is uncompromising.

When they sat down the diamond sector and allowed a “conflict free” narrative without truth, reconciliation and restitution to impacted communities, they risked their credibility. About ten years later, they lost the Faustian Bargain (see theSixth Russian Doll: Kimberley Process’ Damn Lies.)

A year later, we have Responsible Jewellery Council’s Grandfather Clause, as shown earlier, and not a peep came from the NGOs when this was announced.

Yet there can be no ethical jewelry without truth, reconciliation and restitution for past atrocities.

As Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar; it comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.”

We need to start over, fresh.

In working with the Responsible Jewellery Council and accepting the past, the best possible hope is merely flinging coins to beggars. We need to change the structures which produce the beggars.

Restitution is not only fiercely opposing the Responsible Jewellery Council in a manner that impacts disrupts their narrative and impacts their bottom line, but it also means a laser focus on the only small-scale mining initiative that has demonstrably changed the market narrative toward one focused on supporting the small-scale miner: Fairtrade Gold.

Analysis of the jewelry sector in context to human rights and environmental improvement involves grasping not only human rights and environmental issues, but a complex system involving the broader market, market niches, supply chain issues, small-scale and large-scale mining, consumer-facing narratives, bloggers and journalists in the trade and consumer press, and the ethical jewelry market in context to precious metal, diamantes, and colored stones.

It is complicated. You have to be on the inside to understand this gestalt.

If jewelers are in front, and NGOs are supporting their best initiatives, then the jewelry trade can’t claim the NGOs are anti-trade.

Así, we need to build a NGOs, human rights organizations and activist jewelers who are using Fairtrade Gold need to work together to build a new coalition, based uponRevolutionary Love, and athe More Beautiful World Our Hearts Know Is Possible.

I outline the beginning of these steps in theEthical Jewelry Manifesto.C

Explore the full Ethical Jewelry Exposé

**All writing and images are open source, underCreative Commons 3.0. Any reproduction of this material must back link to the landing page, aquí. For high resolution images for publication, contact us at expose(AT)reflectivejewelry.com.**