The Fatal Ineffectiveness Of The Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC) Chain of Custody Scheme

Author’s introduction: This section of the Ethical Jewelry Exposé discussing the RJC Chain of Custody Scheme documents weak enforcement and double standards that allow member companies that have committed atrocities to be certified as “responsible.”

This piece was originally published here.

Wikipedia writes that a chain of custody “refers to the chronological documentation or paper trail that records the sequence of custody, control, transfer, analysis, and disposition of physical or electronic evidence.

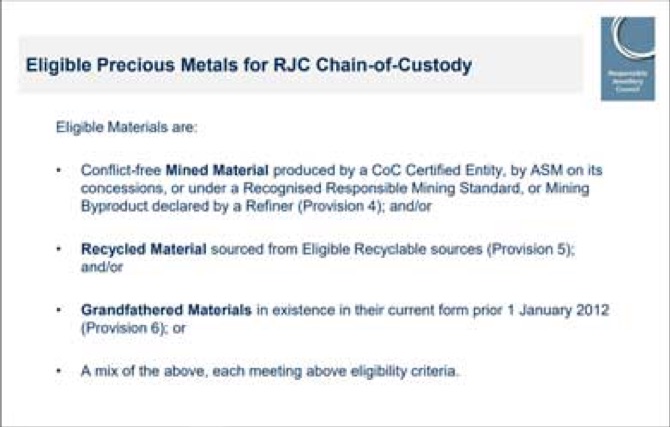

The Responsible Jewellery Council bases their certification on their Chain of Custody scheme.

Basically, certification focuses on the control and transportation of minerals from a mine to the market.

If you have control of your chain of custody, doesn’t that allow for a measure of ethics?

Here’s the problem:

If we accept that traceability and transparency are the sole prerequisites for ethical sourcing, we can ignore past human rights and environmental atrocities.

In other words, even companies that have committed crimes against humanity can be certified as “ethical” under a strictly chain of custody approach to ethics as I pointed out earlier, posting this video about Responsible Jewellery Council ’s certification of AngloGold.

Again, here’s the Grandfather Clause that is, in my view, a cover up for crimes hidden in plain sight.

We can also bypass current environmental, social, labor, or Indigenous rights issues at a particular mining site.

This comes into play because the chain of custody approach regarding how mining companies are certified as “ethical” is company-wide instead of site-specific. Many large-scale mining companies have multiple mines in multiple countries. They also may be partial shareholders of one mine.

So, gold coming from a highly-regulated mine in Canada can be treated the same as gold coming from countries with weak or corrupt governments, with poor track records of regulating environmental and human rights.

Finally, if chain of custody is your main criteria for defining “ethical jewelry,” and you’re a large company which already controls its chain of custody, you’re basically just “certifying” what already exists.

The fact of the matter is, without certain conditions, a chain of custody certification functions essentially as a diversionary tactic that can cover up atrocities.

Responsible Jewellery Council’s Certified Mining Companies

I’ll give you just a few examples of how ineffective a chain of chain of custody approach can be concerning past alleged human rights violations and environmental atrocities of some of the Council ’s certified mining companies.

I have already noted AngloGold Ashanti’s violations in Ghana, but here is another instance from Human Rights Watch in 2005, which details how in the Democratic Republic of Congo…

“…A leading gold mining company, AngloGold Ashanti, part of the international mining conglomerate, Anglo America, developed links with one murderous armed group, the Nationalist and Integrationist Front…”

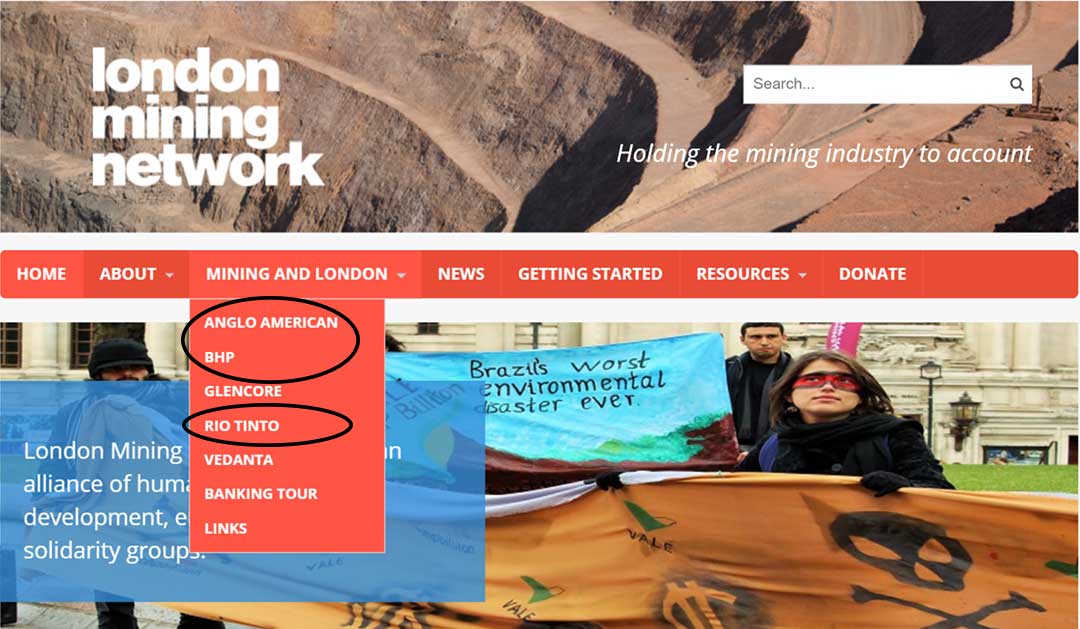

Friends of the Earth International documents Responsible Jewellery Council member BHP Billiton in “An Endless Crime: BHP Billiton and Vale’s Sludge Still Harming Brazil.”

This London Mining Network study, “BHP Billiton: Undermining The Future” highlights the “disparity between BHP Billiton’s ‘Sustainable Development Policy’ and the reality of their operations.”

This blistering critique from IndustriALL Global Union alleges human rights violations and environmental atrocities of Council member Rio Tinto.

How about certified Council member Newmont Mining Corporation, the second-largest gold producer in the world? They allegedly illegally seized land from Indigenous people in Peru, as determined by Peruvian courts, in order to create a five-billion dollar gold mine.

Yet I see no evidence that this incident was investigated under the Council’s code of conduct.

According to this report published on Truthout.org, Newmont sued, harassed, and intimidated community members who opposed their Conga Mine. This Earthworks blog reports that that company’s own study showed their Peruvian subsidiary ignored human rights standards.

Gold Rush: How the World Bank is Financing Environmental Destruction documents alleged issues at Newmont’s Yanacocha mine, also in Peru. “Trout and frogs have disappeared from the waterways, the farmers say. Sometimes, locals say, their livestock refuse to drink from streams that irrigate their land — or they drink the water and then get sick or die.”

Ignoring these issues is actually part of the Council’s Grandfather Clause.

Dirty gold from past atrocities, blood diamonds, and even recycled gold (greenwashed dirty gold) are grandfathered in!

OK, OK, despite all this, there’s still validity to the chain of custody approach, right?

Let us for a moment approach Council with the generous spirit of many of my ethical jewelry colleagues. “It’s all going in the right direction…” We just need to work together.

Let’s ignore the issue of the past. Surely there is some benefit to being able to trace minerals based upon a single company’s mined product, and there is veracity in their certification process?

And, surely a certified mining company goes through a real audit process?

Well, the London Mining Network points out here that the first mining company certified by the Council was Rio Tinto. This took place without an auditing or certification process, in 2012, just in time to supply gold to produce Olympic medals.

London Mining Network also points out Tinto’s environmental and human rights atrocities, which would not be relevant in a purely chain of custody-focused certification scheme.

This 2015 exposé from Ojo Público documents how two certified Responsible Jewellery Council mining companies, Metalor and Italpreziosi, processed illegal dirty gold from the Amazon through to international markets. No control of chain of custody there, yet they are still certified…

(Shreema Mehta of Earthworks uses this example in her article to again make the point that the Council should be “Ensuring that affected communities, unions and civil society groups have an equal seat at the decision-making table. Consultation and invitations to participate in subcommittees are not enough.” Her suggestion is that the Council “clean up its act” by “issuing certificates to specific mines and factory sites, not corporations,” and “immediately cancelling Metalor and Italpreziosi’s certificates.”)

These two more recent investigative articles from April, 2018, (both in Spanish) from Ojo Público and La República document how Council member Metalor continues to operate illegally.

This kind of lack of oversight is why industry watchdogs have argued that the Council multi-sector process designed around traceability and transparency lacks veracity.

The Dirty Details

Let’s dig in as to how standards which seem solid on the outside are not so effective. The 2018 HRW Report notes that:

“Once the auditors complete their report, they only submit a summary report of the audit to the RJC, not the full audit report, which is shared only with the company. Based on the summary report and the auditor’s recommendation, the RJC then determines whether a company should be certified. The RJC does not make the audit or its summary public. allowing companies to be RJC -certified even if they fail to meet basic human rights standards.”

They also state:

“…the Code of Practices allows companies to exclude facilities from the scope of its certification where it does not have full control, meaning more than 50 percent ownership. As a result, certification may exclude operations of significant size. For example, Rio Tinto has excluded the Grasberg gold mine in Indonesia, of which it owns 40 percent, from its RJC certification scope. The Grasberg mine has been the site of numerous deaths of workers and other labor rights issues.”

The Responsible Jewellery Council’s core function as a trade association, a collaboration between companies, overrides the veracity of their own self-generated and highly controlled standards-setting model.

10,000 Critical Breaches

Finally, let’s conclude this section on the Responsible Jewellery Council with a few more lines from that 2009 Michael Rae interview:

Greg Valerio: “Are you saying that if a large-scale mining company like Rio Tinto, who was a founding member of RJC failed to meet the standards in the mining supplement, you would throw them out?”

Michael Rae: “Yes, we would have to. The organization would have no credibility unless there is a consequence to failing to conform with the standards that are set down. And like any other similar sort of system, we talk about critical breaches needing to be brought to our attention and can result in expulsion.”

What kind of “critical breaches” would actually result in expulsion? Not environmental issues. Not human rights issues. How about alleged complicity in genocide?

For forty-five years, Rio Tinto was the majority shareholder of the Panguna mine in New Guinea, which this article from ABC News states was operated under ‘slave like’ conditions”—and was the location of the Bougainville genocide, which claimed the lives of 10,000 people. Tinto tried to get out of the lawsuit resulting from the massacre, but the 9th Circuit Court upheld the plaintiff’s complaint.

Here’s some info on the historical context of this mine—and another resource, outlining a litany of Rio Tinto’s issues, including their hiring of Henry Kissinger to sort out some problems.

(On top of all this, the mine was an environmental catastrophe—but in 2016, according to Papua New Guinea Mining Watch, Tinto walked away from its environmental responsibilities.)

I always find round numbers, such as 10,000, particularly perfidious.

Why not 10,032? Or 10,181? If these were American casualties, we would expect this kind of precision.

In the Bougainville Manifesto, Leonard Fong Roka provides social and historical context to the genocide. He puts the number at between 10,000 and 15,000 people:

“Bougainville was caught up in the imperialist search for raw resources for industrialisation in Europe. From the simple barter of copra to European goods, the trade moved to labour exports, to the development of plantations on Bougainville and then to labour imports into Bougainville. This process secured Bougainville and Bougainvilleans for exploitation and the subjugation of their land. We became nobodies.”

“WE BECAME NOBODIES.”

Let us take a current example for comparison. I am 100% certain that every serious ethical jeweler feels moral outrage at the immigration policy which has separated children from their parents.

Yet the pain of those children we see in articles is minimal compared to the pain that would be caused in a scenario in which the parents or children were killed.

These round numbers, rough estimates of the deaths of Indigenous people, are easily glanced over without the slightest proximity to the pain.

But the proximity is important. It’s grabbing a live wire that leads to the heart of jewelry sourcing, and terrible awe at our collective human experience which jewelers working on ethical issues must be willing to latch on to if we are to be real change agents.

These numbers and their vague estimations underscore the point that that the lives of those Indigenous, dark-skinned people seem to not matter. These are just “nobodies”.

Michael Rae and the Responsible Jewellery Council, and all those who support them, do not see the incident or other past issues which require true investigation, truth, reconciliation, and restitution, as “critical breaches.”

The nobodies are powerless, past and voiceless ghosts.

Explore the Entire Ethical Jewelry Exposé

**All writing and images are open source, under Creative Commons 3.0. Any reproduction of this material must back link to the landing page, here. For high resolution images for publication, contact us at expose(AT)reflectivejewelry.com.**