Death of the Fair Trade Diamond

(This excerpt from Marc Choyt’s Ethical Jewelry Exposé: Lies, Damn Lies, and Conflict Free Diamonds, was originally published here.)

NGOs have pointed out for decades that large-scale mining is destructive to the culture and environment of Indigenous people. It has become absolutely critical that large multinationals that have a public profile present strong examples of their concern for small producers.

Inside the Fifth Russian Doll we find the Non-government organizations who work with Council and therefore lend it legitimacy.

The Council has signed memorandums of understanding with two prominent NGOs, the Alliance for Responsible Mining (ARM) and The Diamond Development Initiative (DDI). These function as focal points, to demonstrate to the world that the Responsible Jewellery Council cares about the small-scale miner.

The inclusive path, as illustrated by this Council document, as well as the screenshots of the Council ’s homepage referenced earlier, show how large- and small-scale are working together.

These relationships are particularly effective from an ethical jewelry marketing point of view. They allow the mainstream jewelry trade to loudly, boldly declare just how much they are doing, magnifying the impact of these two small programs in a continual flow of positive stories.

These new stories deflect the criticism that the jewelry sector does not support small-scale mining and creates a new forward-facing narrative for the gold from their newly-branded “ethical” large-scale sources.

Let me put it another way, more bluntly:

This is the new ethical strategy of mainstream jewelry sector’s leaders—benefit a few small-scale miners, scream and shout about it to the world so that you can continue to screw over the rest just as you always have.

Now, two examples that will illustrate my argument…

The Alliance for Responsible Mining

The Responsible Jewellery Council’s first small-scale mining partnership is with the Alliance for Responsible Mining, which focuses on building capacity among artisanal and small-scale miners. In addition to their formal memorandum of understanding, Felix Hruschka sits on both Responsible Jewellery Council ’s Standards Committee and the Alliance for Responsible Mining board.

These days, the Alliance for Responsible Mining and the Responsible Jewellery Council, as we will explore, are as complementary and coordinated in their messaging as two strands of the same DNA. Yet it is impossible to understand the implications of this partnership without some sense of events leading up to the present.

The Alliance for Responsible Mining started out as a gritty advocate of small-scale miners, working to create standards and principals that could allow ethical gold to reach an international market.

In 2009, the Alliance for Responsible Mining joined Fairtrade to create a joint standard, as I reported here. Together, they introduced Fairtrade/Fairmined Gold to the UK in 2011.

Fairtrade/Fairmined Gold, for reasons I detail in my supplementary Article, Fairtrade/Fairmined in the US/UK, was the single most important breakthrough in the ethical jewelry movement.

For Fairtrade International, it was radical. Up to that point, Fairtrade had only certified agricultural products. But working with the Alliance for Responsible Mining, they were able to branch into the mining sector.

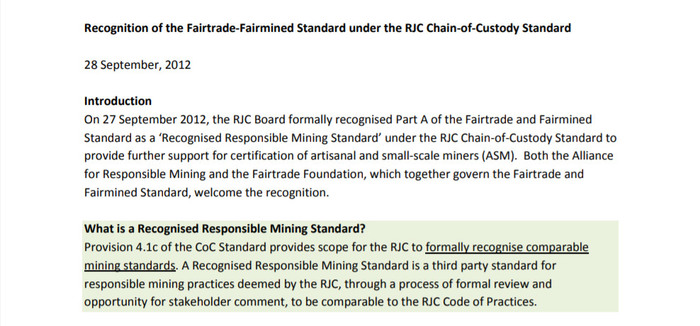

In 2012, the joint Fairtrade/Fairmined standard for small-scale mining was recognized as legitimate. That same year, the Council and Alliance signed a memorandum of understanding.

Screenshot from the Council’s Website.

At that junction, activist jewelers, myself included, were optimistic that this move might bring greater clout to the Alliance for Responsible Mining’s efforts to make small-scale mining a prominent issue in the mainstream—yet we were also concerned about how Responsible Jewellery Council’s reputation might hurt the Fairtrade Gold brand.

I outlined these concerns in my post at the time, the courtship of the Alliance for Responsible Mining and the Responsible Jewellery Council —in which I point out that the Alliance’s alliance with the Responsible Jewellery Council ultimately betrayed the powerful alignment between small-scale miners and pioneer ethical jewelers.

My organization, Fair Jewelry Action, organized this petition to the Alliance for Responsible Mining and Fairtrade against mass balancing, which would have involved mixing gold from responsible small-scale mining with other gold sources. 140 companies signed it.

I felt it was critical for the consumer-facing narrative—in the selling of a wedding ring, for example—that the gold itself be directly traceable to a particular certified mine. In my store, when I have a customer looking for a gold wedding ring, I tell them the story of Macdesa—the present source of our Fairtrade Gold.

If, instead, I had to say a ring was made with gold partially mined at Macdesa, as well as gold from some other, unknown source…it doesn’t have quite the same…ring? Sorry. Quite the same ethical authority.

We were fighting for a new narrative, a new story. Linking a piece of jewelry to a source is a powerful, radical, transformative narrative. Linking the ethics of small-scale mining gold to the ethics of large-scale mining undermined the consumer-facing narrative. Such a move was an extreme threat to a broad ethical-based jewelry movement grounded in small-scale producer-centered benefit.

In 2013, the Alliance for Responsible Mining and Fairtrade split their label. Certainly, one of the causes for this division was the mass balancing issue. Fairtrade began a process of solidifying their international gold program, working with miners and retailers to design a viable commercial platform which would allow the expansion of the market.

Now, Fairtrade Gold and Fairmined Gold are competitors.

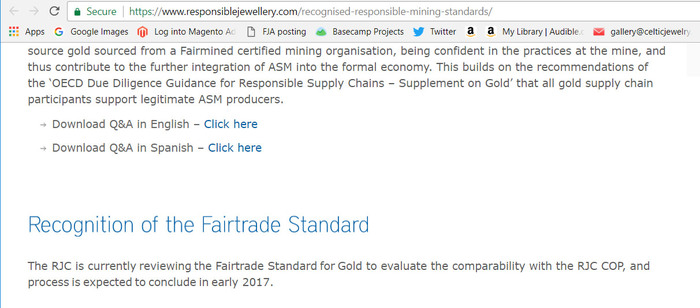

Yet, even through 2017, the Council still did not accept Fairtrade’s standards as legitimate even though, as mentioned above, they recognized the Fairmined/Fairtrade standard in 2012 and since then there has been virtually no significant on the ground difference between Fairtrade and Fairmined mining certification.

It needed to review the Fairtrade Standard “to evaluate the comparability with the RJC COP, and process (sic) is expected to conclude in 2017.” (COP = Code of Practice.)

This screenshot was taken on December 31, 2017.

A good joke! Five years for the Responsible Jewellery Council to review whether Fairtrade’s standards are up to their code, which they said were fine in 2012?

There is a strong consensus, particularly among ethical jewelers, that we should not choose sides between Fairmined and Fairtrade. That we should treat them all equally. Yet there has been ZERO outcry from jewelers advocating for the entire small-scale mining sector that the Responsible Jewellery Council has not advocated for Fairtrade Gold.

Imagine if jewelers had demanded that the Council at least endorse the legitimacy of Fairtrade Gold before this year—what a boost it might have been for small-scale miners, as large companies could have joined the Fairtrade scheme.

Yet this did not happen, because Fairtrade is not controlled or beholden to the Responsible Jewellery Council, which is exactly why ethical jewelers should go with the Fairtrade standard over Fairmined.

PS: It was only in January 2018 that Fairtrade Gold was accepted as a legitimate standard by the Responsible Jewellery Council that meets its “code of conduct!”

Chopard’s Fairmined “Responsible” Practices

Yet the most profound influence of the Responsible Jewellery Council/Alliance for Responsible Mining collaboration is that the small-scale story has been blended to add credibility to the Responsible Jewellery Council’s “responsible gold” initiative.

Even more harmful than mass balancing gold is what I would call a kind of “mass balancing the consumer-facing narrative” in relation to small-scale gold mining.

The big recent news on the ethical jewelry front is Chopard’s announcement that all their gold will be “100% ethical.” Chopard is a luxury watch maker.

First, take a look at this screen shot:

Any guesses who might be behind the Chopard initiative? Just to be clear…

Responsible Gold Is Knocking At The Door!

Chopard took five years to launch their initiative. They had a massive inventory of watch casings, bands, etc, that are made of “unethical gold.” These needed to be replaced with the new “responsible gold.”

Chopard’s website (see the screen shot below) explains how Fairmined Gold is used in their product currently.

But let’s look more closely at the Chopard initiative, as explained in this article from Barrons:

“By July, all the gold the company buys will be traceable to small-scale mines that are part of certification systems set up by Alliance for Responsible Mining’s Fairmined, the Swiss Better Gold Association or Fairtrade, or to mines and other suppliers that meet the Responsible Jewellery Council’s “Chain of Custody” standards.” (Italics mine.)

First, notice the structure of the narrative. Fairmined is first. Then second, as a corollary, we’re told of other suppliers that meet the Responsible Jewellery Council’s chain of custody.

Outside of what is used by Fairmined, Chopard’s “responsible” gold comes from Responsible Jewellery Council members. (See the Fourth Russian Doll: Responsible Jewellery Council Chain of Custody Scheme for a full critique of the Council’s chain of custody approach.)

This Vogue article, quoting Caroline Scheufele, explains how they purchase Fairmined Gold “from 5 percent to 10 percent more than the stock market”—yet it won’t affect the price. As a jeweler, I suspect that the 5%, might add $25 to $50 to a product’s cost of goods.

An August 24th, 2018 article on Chopard’s initiative, aptly titled “Going Beyond Ethical Gold,” states:

“The move will narrow Chopard’s choice to two sources of gold for its jewellery and watches: artisanal freshly mined gold from small-scale mines participating in the Swiss Better Gold Association, Fairmined and Fairtrade schemes; and RJC Chain of Custody gold, through Chopard’s partnership with RJC-certified refineries.”

A luxury brand is essentially anchoring the consumer narrative that small-scale gold is equally ethical to Council’s supply chain, and this initiative is reinforced by journalist and bloggers.

For example, this article in Vogue lauding Chopard states, “The RJC certification doesn’t guarantee traceability, but the latest version – released at the end of 2018 – will do its due diligence by outlining the steps certified members have to take to avoid exacerbating conflict and violating human rights.”

Chopard’s Co-president Karl Scheufele speaks of the initiative in emotional terms. We are told that it is a family business…sustainability has always been a core value…ethical gold is the culmination of a 30 year vision. “It is a bold commitment, but one that we must pursue if we are to make a difference to the lives of people who make our business possible.”

He is also endorsing the Grandfather policy referenced earlier, in which reiteration of colonial business practices are granted impunity—an impunity which hides alleged crimes that can be clearly viewed.

There is no question that Chopard’s high-profile initiative helps some small-scale mining communities. It may be that Chopard does not fully understand the weaknesses of the Responsible Jewellery Council’s certification. Their endorsement of the new “responsible gold” could be a reputation risk if the public understood what’s taking place.

Yet for now, the amount of gold certified by Alliance for Responsible Mining, which the Responsible Jewellery Council will squeeze every possible ounce of publicity out of, is a tiny fraction of the total gold produced by Council members. Yet this fraction is the new face of “responsible gold.”

“Responsible gold” essentially creates a new narrative of Fairmined Gold from small-scale miners and the large-scale multinationals. Because the Responsible Jewellery Council “responsible gold” brand is anchored by Chopard’s narrative, Fairmined Gold = Responsible Jewellery Council’s new “responsible gold.”

The Diamond Development Initiative

The Diamond Development Initiative is the second small-scale mining group that Responsible Jewelry Council signed a memorandum of understanding with in 2011.

Any critique that the jewelry industry is not doing enough for small-scale diamond miners is answered by the Initiative.

The Diamond Development Initiative began in 2005, from a UN meeting with representatives from governments, UK and US aid agencies, and NGOs. A coordinating group was formed, and in 2007, the initiative was passed to a board of directors and advisory group.

In January 2008, the Initiative appointed its first Executive Director, Ian Smillie, author and development consultant who helped form the Kimberley Process.

The Initiative was “created to address the social and economic issues faced by millions of artisanal diamond diggers in Africa and South America who live in poverty outside of the formal economy.”

Smillie, here in 2008, framed out the purpose of the Initiative by asking the question: “Why are people talking about “fair trade” diamonds?” He references FLO (Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International, aka Fairtrade International.)

His words provide a concise summary of the issues at hand:

“The Diamond Development Initiative (DDI), a non-profit organization bringing together civil society, governments and industry, was created to deal directly with this challenge: to test and apply development solutions to development problems. Instead of treating diggers as criminals, the idea is to find ways of bringing them into the formal economy where they can have a long-term stake in a legal system and real benefits.”

To be clear, the challenges of the Initiative in creating a fair trade diamond are formidable, as can be explored in this Fair Trade Diamond Feasibility Study, which was also completed in 2008. This study was conducted by TransFair USA (now Fair Trade USA) and funded by a $100,000 grant from The Tiffany & Co. Foundation.

The study recognized that, “the business case for Fair Trade Certified (FTC) diamonds is generally positive; it is clear from the marketing study that there is strong interest for buying and selling FTC diamonds amongst mission-based retailers, who anticipate growing customer awareness and demand” (p. 3).

The Diamond Development Initiative has focused on Sierra Leone, one of the countries most impacted by diamond-funded war. With major industry backing, the initiative has had resources necessary to accomplish its goal.

Yet…a redemptive diamond narrative focused on the plight of small-scale diamond diggers, whose communities had been impacted by wars funded by diamonds, would be highly disruptive to the “a diamond is forever” narrative.

Thus, the years passed by…and no FTC diamond ever came to market.

In 2016, the Diamond Development Initiative introduced the Maendeleo Diamond Standards, which outlines on-the-ground practices necessary to bring ethically-sourced diamonds to market.

The 2018 version of these standards states the objective to create a process “that promotes sustainable development and responsible mining practices at artisanal and small-scale diamond mines. This improves the lives of the miners who dig artisanal diamonds and benefits the broader communities to which they belong.”

It was hard not to conclude that, after ten years without a diamond brought to market, it was merely some decoy jewelry trade leaders could point to and say, “We care about the small-scale diamond sector. Just look at the Diamond Development Initiative.”

The Diamond Development Initiative in 2018

To understand the agenda of the Diamond Development Initiative, we need to look at the Diamond Development board. Ian Smillie is still chair. Among others, membership includes Matt Runci, former Chair of Governance for the Responsible Jewellery Council and CEO of Jewelers of America. Also, there’s John Hall, CEO of Corporate Reputation Strategy and former GM of External Relations for Rio Tinto.

The question then becomes: under what conditions would the Responsible Jewellery Council (and its member, De Beers) allow a viable diamond from ASM mines to reach the market?

Obviously, two critical elements must be in place:

First, they must have control of the market. Control of the market means control of the number of diamonds and how they are distributed through jewelers to the public.

Second, and perhaps even more important, is to control the narrative story. Ethical sourcing in the diamond sector is an area of great vulnerability to diamond marketing. A fair trade diamond, as Smillie suggested when he referenced FLO back in his 2008 statement, would be disruptive to the market.

Market control has historically been De Beers’ specialty. You’d better believe that if there was going to be a fair trade diamond, particularly out of Africa—their home turf—they would have their hand in it.

Now, let’s explore the Diamond Development Initiative/Responsible Jewellery Council Alliance

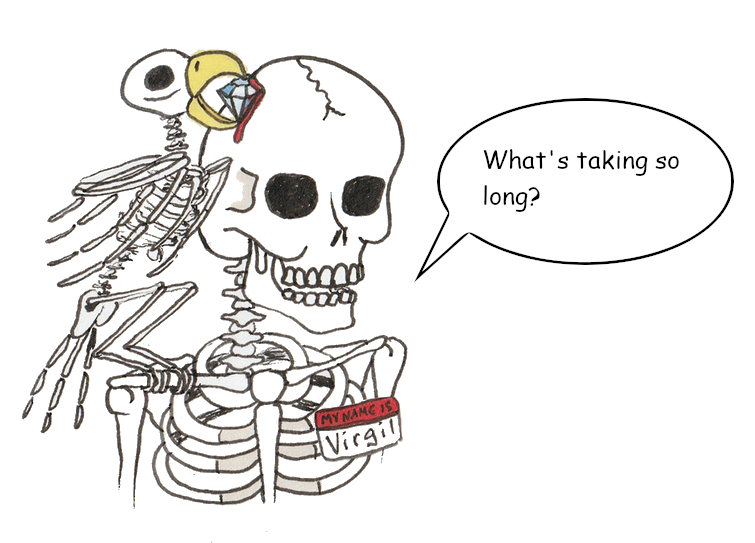

We can start with the Initiative’s pro-Kimberley Process agenda…here’s a Tweet. This one took place when IMPACT pulled out of the Kimberly Process:

The Diamond Development Initiative, as an advocacy group for small-scale diamond miners, does not acknowledge the Kimberley Process’s incurable faults that led to the only legitimate Non-governmental Organization on its counsel left to abandoned it, but instead “regret[s]” the announcement.

IMPACT was one of the key stake holders in the Kimberley Process (when IMPACT was then called Partnership Africa Canada)—through the leadership, at that time, of Ian Smillie.

Here is its statement from its current ED Joanne Levert upon leaving the Kimberley Process:

“The Kimberley Process—and its Certificate—has lost its legitimacy. The internal controls that governments conform to do not provide the evidence of traceability and due diligence needed to ensure a clean, conflict-free, and legal diamond supply chain. Consumers have been given a false confidence about where their diamonds come from. This stops now.”

IMPACT waited seven years to conclude what Global Witness, another key framer of the Kimberley Process, understood in 2011, when they resigned over the Kimberley Process’ certification of blood diamonds from Zimbabwe.

Global Witness in context to Zimbabwe is explored in another section, but for now, note Global Witness’ 2011 Press Release: “The Kimberley Process’s refusal to evolve and address the clear links between diamonds, violence and tyranny has rendered it increasingly outdated.”

Yet, the January 2018 tweet shows that Ian Smillie, one of the most important and respected global champions of small-scale diamond miners, now, through the Tweet of his organization, endorses the Kimberley Process.

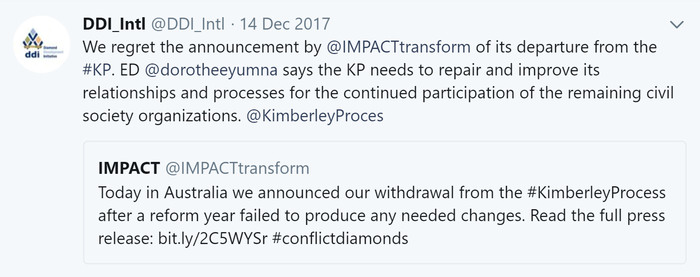

But now, look at this retweet:

It shows the Diamond Development Initiative’s connection to De Beers. I did not fully understand why the Initiative was retweeting De Beers until this announcement went up from De Beers.

The Diamond Development Initiative’s partnership with De Beers allows De Beers to leap into the artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) diamond market through this joint GemFair initiative.

The Death of the Fair Trade Diamond

The diamond from the Diamond Development Initiative will now will find its market through De Beers.

As stated in the GemFair press release, “Any approved purchases would be sold via De Beers’ industry-leading Auction Sales channel.”

Part of this initiative is to equip small-scale miners with blockchain equipment that would allow them to mark the location of where a diamond is found.

(From a business point of view, offering this equipment for free is considerably cheaper and carries far less reputational risk for De Beers than hiring paramilitary groups, as they did between 1980 and 2000.)

If this initiative were put into place by Fairtrade International, I would be cheering. But it was not, and I am not. Here’s why:

The Initiative has spent massive resources over the past thirteen years to build capacity in their small-scale mining communities. This is a valuable kind of collateral, and it previously belonged to the broader community of people who supported it. Now, with GemFair, it is functioning as a nonprofit arm of De Beers.

Though what is happening in Sierra Leone is an excellent example of what can be done for small-scale diamond diggers, it is entirely contained. Whether De Beers is going to brand this diamond separately or simply fold it into their supply chain has yet to be determined. It’s a perfect showcase for the diamond sector to show the world that it cares.

The spin coming from De Beers is that if this initiative succeeds, there’s the possibility it can expand into other countries. Really? The Sierra Leone project took over ten years. Honestly, I would find it ludicrous to believe that the project will expend to other areas. The million other small-scale diamond diggers around the world living in poverty—as well as the larger consumer market genuinely craving a fair trade diamond, will not get what they want.

Regardless, De Beers has absolute control of the market narrative, and it is a certainty that this new diamond will have no impact on their current branding.

In essence, over the past ten years, the Diamond Development Initiative has gone from a fair trade model to a De Beer’s controlled initiative.

Suppose all Fairtrade Gold was purchased by De Beers and sold exclusively through De Beers. Would you believe it? In fact, if the industry was really interested in a fair trade diamond, they could have supported Fairtrade International in creating a program like Fairtrade Gold.

The irony is thick. With the Diamond Development Initiative, De Beers creates a monopoly on the new frontier of ethical diamonds: the traceable small-scale sector, the very sector that that they controlled during the ‘80s when millions were being killed.

De Beers is, as this recent trade magazine article points out, implementing a strategy “in an effort to monopolize the market in diamonds that are ‘ethical.”

Of course, Brilliant Earth, the company that dominates the American ethical jewelry space, speaking directly to the ethical millennial consumer, amplifies and legitimizes the Diamond Development Initiative’s work—already laying the ground for the new “Vision For The Future: Fair Trade Diamonds.”

Here’s a screenshot from their website:

Screenshot from summer 2018.

In my opinion, considering the historical context, giving De Beers control of the Diamond Development Initiative’s new, as Brilliant Earth calls, “fair trade diamonds” is like putting David Duke in control of the Southern Poverty Law Center.

But to understand how this event is the end of a coherent strategy that has been taking place for years, we must open the next Russian doll and explore the diamond babble.

Explore the full Ethical Jewelry Exposé

**All writing and images are open source, under Creative Commons 3.0. Any reproduction of this material must back link to the landing page, here. For high resolution images for publication, contact us at expose(AT)reflectivejewelry.com.**